Kristóf Kelemen travelled to Vilnius.

Budapest’s second artist Pál Kárpáti travelled to Istanbul.

Artist’s statement

As theatre maker I create research-based projects, such as documentary theatre, lecture performance, fictional drama or interactive theatre quizes with different types of collaborative methods, and these very diverse artistic experiences show me over and over new perspectives of historical times and contemporary life. The monumental literary project of Ulysses also presents the wide range of styles, voices and perceptions of reality with a complex network of references. This masterpiece of Joyce, as a celebration of diversity, is a great symbol and a leading light of cultural cooperation between European nations. I find the artistic exchanges in the project of “ULYSSES European Odyssey” an inspiring opportunity to get to know another city’s history and present time, cultural institutions and local problems that could show me interesting connections between different nations’ issues and common points of challenges.

Artist’s Biography

Kristóf Kelemen was born in Pécs, but has been living in Budapest for more than a decade. He graduated as a dramaturg from the University of Theatre and Film Arts in Hungary’s capital, and later received his doctorate from the same university. In the course of his theatre work, he’s tried his hand at a variety of tasks: as a director and writer of theatre productions, as a lecture-performance artist, and as a creator of collaborative projects. His performances vary both in form and genre, and he sees everything he works on as an experiment, a creative adventure. He’s produced documentary theatre, interactive theatre quizzes, fictional drama and guided tours with online live performances. His work is research-based and explores contemporary social and political issues, while addressing less prominent historical moments. His performances have been showcased at a number of international festivals, including Fast Forward in Dresden, Spielart in Munich and Theaterfestival Basel.

More info

I spent two weeks in Lithuania on an artist residency thanks to #budapestbrand and @vilniausmuziejus. I published some posts about my impressions related to the history and geography of Lithuania which I got to know during my trip from Vilnius to the Baltic Sea. I have created a video (see below) about the installation of the project Vilnelé Odyssey in Markučiai and about the rivers that flow through the whole country.

Thanks to @zi.vile.mi for the interesting tour and nice company in Vilnius.

Video from the visit

Visual Gesture

Each artist on the residency programme was asked to create a simple visual gesture for potential inclusion in the ULYSSES European Odyssey book. An image that reflected their visit to another partner city, a moment which stayed with them, something quite simple, even symbolic.

All images are copyright of the individual artists.

A Budapest Brand Staféta-közönségdíjával külföldi rezidencialehetőséget nyertem, amelyet Litvániában töltöttem el 2023. augusztus 7-21 között, ahol a Vilniaus Muziejus fogadott. Ennek keretét egy nemzetközi együttműködés, az „ULYSSES European Odyssey” projekt adta, amelynek megvalósult köztéri installációit is megtekinthettem Vilniusban. Továbbá az ottlétem alatt igyekeztem minél jobban megismerni a régió történetét, számos hasonlóság fedeztem fel a miénkkel, de igazán érdekesek a különbségek voltak.

Míg Magyarország önálló állam maradt az államszocializmusban, a Baltikum beolvadt a Szovjetunióba. Litvánia részei a történelem során vagy a németekhez, vagy az oroszokhoz, vagy a lengyelekhez tartoztak, ezért a Szovjetunió felbomlása utáni nemzeti függetlenséget nagyon nagy becsben tartják. Érdekes volt megtapasztalni, hogy a mélyen keresztény és nacionalista eszméken nyugvó litván patriotizmus hogyan vezet ahhoz is, hogy a nemzeti önképükben az ellenállás, a partizánmozgalmak és az autonómia a legfontosabb értékek.

Ez mutatkozott meg a KGB Museumban Vilniusban, amelyet egy nagyon hasonló történetű épületben rendeztek be, mint amilyen Budapesten a Terror Háza (a nácik majd a szovjetek is bebörtönöztek és kínoztak itt embereket). De míg a Terror Háza a szenvedésre és az áldozatokra helyezi a hangsúlyt, a vilniusi múzeum inkább az ellenállásra koncentrál. Több terem is foglalkozott a partizánok életével.

A Dél-Litvániában található Grūtas Park a budapesti Memento Parkhoz hasonlóan ironikus keretben állítja ki az egykori kommunista szobrokat, amik az erdőben állnak – mintha a természet fokozatosan magáévá tehetné ezeket a romokat. A hely érdekes megközelítését prezentálja annak a kérdésnek, hogy hogyan tudunk úgy emlékezni, hogy nem kitöröljük a múltunkat, mégis újrakeretezzük azt. A parkban van egy állatkert is, tehát baromfihangok övezik a sétát a monumentális Leninek között.

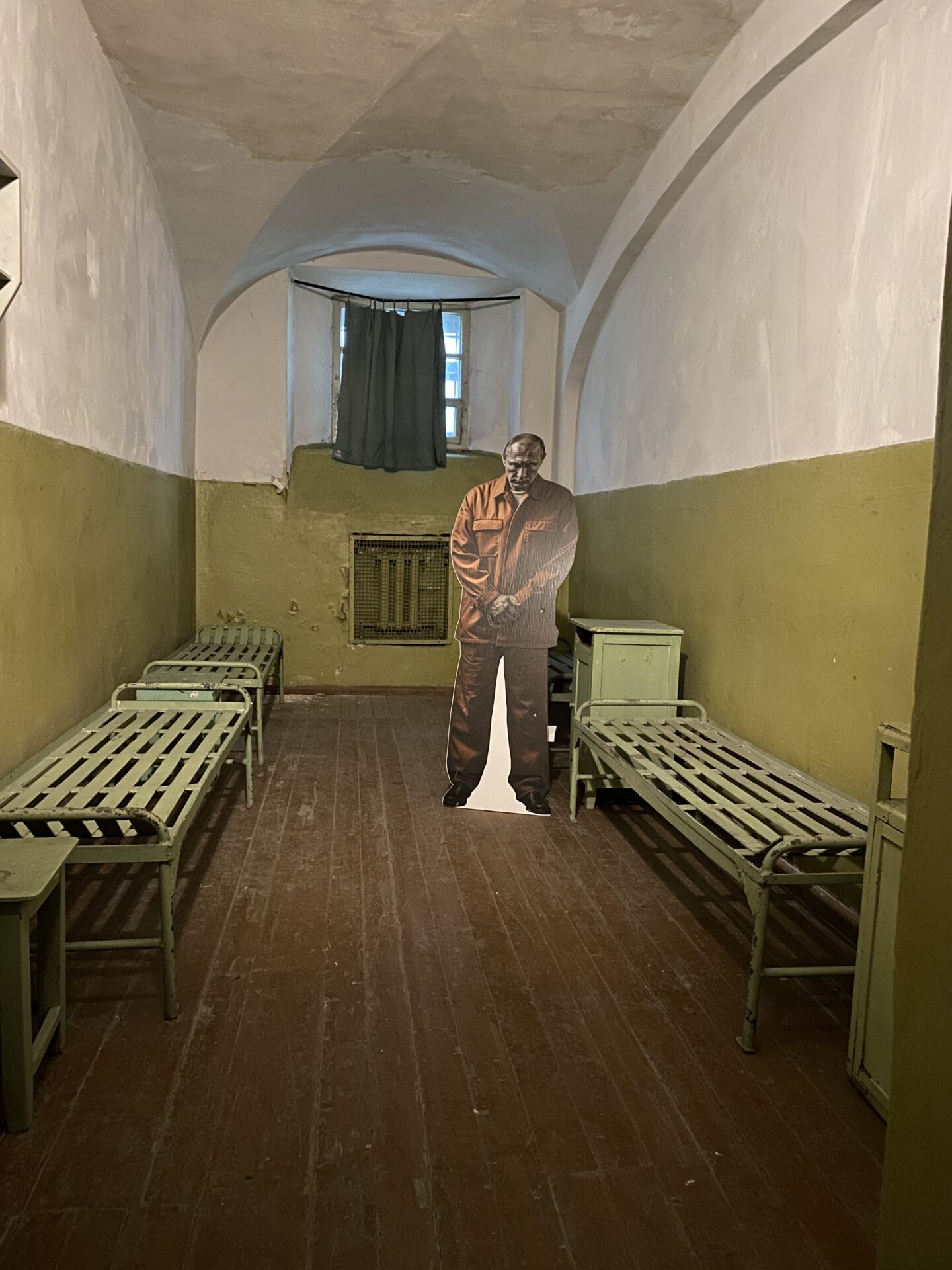

És visszatérve az ellenállásra: Litvánia nagyon látványosan kiáll Ukrajna mellett, pl. a KGB Museumban egy papír-Putyin áll az egyik cellában, aki mintha már most az egykori szovjet börtönben töltené a büntetését. Szuper lenne, ha ilyen reprezentatív intézmények nálunk is megengednének maguknak hasonló fricskákat.

Šiauliai közelében a Keresztek hegye nemcsak zarándokhely, hanem az ellenállás szimbóluma is. A budapesti Eleven Emlékműhöz hasonló önszerveződő emlékhely kezdetei a 19. századra nyúlnak vissza, amikor az orosz megszállás idejében kivégzett litván ellenállóknak nem tudták a sírhelyét, ezért elkezdtek itt kereszteket állítani nekik. Majd ez a hagyomány akkor sem tört meg, amikor a II. világháború után, az újbóli megszállás során a szovjet hatalom több alkalommal is mindent megsemmisített buldózerekkel – az emberek visszajártak és újra és újra visszaépült a Keresztek hegye is.

A rendszerváltás után II. János Pál pápa látogatást tett itt, ezzel is kiterjesztve a katolikus egyház territóriumát Litvániára, amely a történelme során nemcsak politikailag, hanem vallásilag is alávetett helyzetbe került az oroszoknak és az ortodox egyháznak – mint ahogy a mostani ukrajnai háború sem csak a politikai hatalomról szól, hanem vallásháború is.

Az utazásom során eljutottam a Balti-tengerig, ahol a litván tengerpart legérdekesebb üdülőhelye Nida, amely a Kur-földnyelven (Curonian Spit) helyezkedik el. Ezt a furcsa félszigetet csak komppal lehet megközelíteni Litvániából, mivel a kontinenshez csak orosz földön keresztül kapcsolódik – a Kalinyingrádi területeken, Oroszország exklávéjában. A földnyelv egyik vége litván, a másik orosz – és mivel Litvánia lezárta a határait Oroszország felé, ezért egy ponton az út véget ér. Tehát az orosz határ mellett található a megrendítően nyugodt Nida, Thomas Mann egykori nyaralóhelye, amely a földnyelv egészével együtt futóhomokra épült. A dűnék az évszázadok során több falvat is elnyeltek, Nidának a 18. században arrébb kellett települnie a homok elől. Azóta különféle fásítási programokkal igyekeznek szabályozni azt, de a klímaváltozás és a sokszor pusztító turizmus miatt az útikönyvektől a táblákig mindenhol kommunikálják, hogy ha nem vigyázunk, talán egy napon az egész település eltűnik a dűnék alatt.

Kelemen Kristóf

With the Budapest Brand Relay audience prize, I won a residency opportunity abroad, which I spent in Lithuania between August 7-21, 2023, where I was hosted by the Vilniaus Muziejus. The framework for this was provided by an international collaboration, the “ULYSSES European Odyssey” project, whose public installations I was able to see in Vilnius. Furthermore, during my stay I tried to get to know the history of the region as much as possible, I discovered many similarities with ours, but the differences were really interesting.

While Hungary remained an independent state under state socialism, the Baltics merged into the Soviet Union. Throughout history, parts of Lithuania belonged either to the Germans, or to the Russians, or to the Poles, which is why national independence after the breakup of the Soviet Union is held in high esteem. It was interesting to experience how Lithuanian patriotism, based on deeply Christian and nationalist ideals, leads to the fact that resistance, partisan movements and autonomy are the most important values in their national self-image.

This was shown in the KGB Museum in Vilnius, which was arranged in a building with a very similar history to the House of Terror in Budapest (the Nazis and then the Soviets also imprisoned and tortured people here). But while the House of Terror focuses on suffering and victims, the Vilnius museum focuses more on resistance. Several rooms dealt with the life of the partisans.

The Grūtas Park in southern Lithuania, similar to the Memento Park in Budapest, exhibits the former communist statues in the forest in an ironic frame – as if nature could gradually embrace these ruins. The place presents an interesting approach to the question of how we can remember without erasing our past, yet reframing it. There is also a zoo in the park, so the sounds of poultry surround the walk between the monumental Lenins.

And returning to the resistance: Lithuania very spectacularly stands up for Ukraine, e.g. in the KGB Museum, a paper Putin stands in one of the cells, as if he is already serving his sentence in the former Soviet prison. It would be great if such representative institutions could afford similar pranks in our country.

The Hill of Crosses near Šiauliai is not only a place of pilgrimage, but also a symbol of resistance. The beginnings of a self-organized memorial site similar to the Eleven Memorial in Budapest date back to the 19th century, when the Lithuanian resistance fighters executed during the Russian occupation did not know where their graves were, so they started erecting crosses for them. This tradition was not broken even when the II. After World War II, during the re-occupation, the Soviet power destroyed everything with bulldozers several times – people returned and the Hill of Crosses was rebuilt again and again.

After the regime change Pope John Paul II visited here, thereby expanding the territory of the Catholic Church to Lithuania, which throughout its history was not only politically but also religiously subordinated to the Russians and the Orthodox Church – just as the current war in Ukraine is not only about political power, but also a religious war.

During my trip I reached the Baltic Sea, where the most interesting resort on the Lithuanian coast is Nida, which is located on the Curonian Spit. This strange peninsula can only be reached by ferry from Lithuania, as it is connected to the continent only through Russian land – in the Kaliningrad Territories, an exclave of Russia. One end of the isthmus is Lithuanian, the other Russian – and since Lithuania has closed its borders to Russia, the road ends at a certain point. So next to the Russian border is the poignantly calm Nida, Thomas Mann’s former vacation spot, built on quicksand along with the entire peninsula. The dunes swallowed several villages over the centuries, and Nida had to settle away from the sand in the 18th century. Since then, they have tried to regulate it with various tree-planting programmes, but due to climate change and often destructive tourism, everything from guidebooks to signs communicates that if we are not careful, maybe one day the entire settlement will disappear under the dunes.

Kelemen Kristóf